On the 25th

of March, 1885, Father Lourdel set out once more for Uganda. It was

difficult to engage porters, for the tribes were still at war in the

country which had to be traversed. They were still in the rainy season,

and the travellers were sometimes waist deep in water.

"To preserve their garments from a wetting,” he wrote, “my

companions took them off, rolled them into a small bundle and fastened

them on their heads. As I could not avail myself of this excellent idea,

I could not help wishing that I had at least a bathing costume. In the

evening of the 3rd of April they reached Ukune, where they received

a hearty welcome from the Uganda neophytes who had been left behind

in charge. The rain had washed away the kitchen and part of the veranda,

but in what remained of the mission house the travellers were able to

take a much needed rest.

"We kept the feast of Easter," writes Father Lourdel, "as

the Israelites celebrated the Pasch, staff in hand. We prayed also that

we might arrive safely, like the Israelites, in our Promised Land, without

falling into the hands of our Egyptians, the Watuta."

There was need of prayer. A few days later, a band of these warriors

attacked a village in the near neighbourhood of the mission, and the

Fathers were able to watch the battle from the roof. Luckily the natives

succeeded in repulsing them, but the way to Kamoga, the next station,

lay right through their country.

On the 15th of April, Father Lourdel set off again, with the catechumens

and the children, through forests and fields devastated by Watuta raids.

On the 17th the porters struck and refused to go further, without lighter

loads and more pay. As Father Lourdel knew that Father Girault was sending

men from Bukumbi to help to carry the luggage, he let them go, and on

the next day sent off three of the Uganda Christians with a trusty guide

to meet the others. Two days later the guide returned alone to tell

the sad tale that they had been attacked by the Watuta, and he alone

had escaped.* The next day they heard the war cries of the Watuta all

round them. The terrified porters declared that they were going to certain

death. Komba, the chief of one of the villages who had offered his house

to Father Lourdel for a morning Mass, now offered to be their guide.

"I think I can lead you safely through" he said, "if

we leave the beaten tracks and take to the forest. It will be a hard

journey, for the forest is deep and the brushwood thick, but it is the

only way to escape the enemy."

* One of the three, Étienne, was

later rescued by the courage and devotedness of Gabriel, another Uganda

catechumen, who risked his life in the attempt to save him.

On the 23rd they left the hospitable village to cross the enemy lines.

Dead silence was prescribed for all, and as much haste as possible.

"Presently," writes Father Lourdel, "a little boy whom

I had bought before leaving Ukune that he might not be separated from

his brother, one of our children, began to cry and said that he could

no farther. It was indeed hard travelling for an eight year old. As

every porter had as much as he could carry, I shouldered him myself,

but after a mile or so found it was more than I could manage and had

to put him down.

Then it was the turn of the dog, who suddenly began to howl in a way

that would have wrung our hearts at a less critical moment, but which

might have been our death where we were. A thorn had pierced his foot,

and as he refused to let it be taken out, I condemned him to be sacrificed,

when he suddenly decided to be quiet and to limp along on three legs.

Halfway through the afternoon the porters refused to go further, and

we had to camp in the forest, lighting fires to drive away the wild

beasts.

The guides now showed signs of fear and were preparing to run away,

but Komba had his eye on them and we went on eastwards. Little Kabouga's

feet were so swollen that he could not walk at all. I put him on the

donkey, to which he clung like a limpet. Then we had to cross an open

space, and were scarcely back under cover when we heard firing. It seemed

to be coming nearer every minute.

"Kombo went on to scout and we followed as he directed. Suddenly

the donkey set to work to bray in his most sonorous voice. Everyone

fell on him, some pulled his tail, some, his head; he was so astonished,

that, to our great relief, he stopped as suddenly as he had begun. The

brave Kombo always scouting, we went on till we had passed the zone

of danger, when he took leave of us and went home. How grateful we were

to this kind friend for all he had done for us. May the Lord reward

him by bringing him to the Faith."

At last they reached Kamoga, and Father Lourdel was trying to make arrangements

with an Arab to transport them across the lake when he heard that Mwanga

was sending twenty boats to fetch them. With them came some of their

first converts, eager to greet the Fathers and give them news of Uganda.

During the two years that had elapsed since their departure, they said,

a hundred and seventy seven of the catechumens had died, after having

been baptised by their friends, but in spite of this, owing to the zeal

of the remainder, the number had not grown less.. Mwanga, they said,

had averred that he was only waiting the arrival of the Fathers to declare

himself on the subject of religion.

On the 25th of June, Father Lourdel, Father Giraud, and Brother Amans

embarked for Uganda. On the shore at Doume they found their old friend

Fuké, who was there at the head of 1,200 men to exact the tribute

due from the chief to Mwanga. He remained with them for a day and a

half, during which time Father Lourdel tried to learn from him as much

as possible of the true state of affairs in Uganda. His account was

less reassuring than that of the others. Mwanga, he said, was ready

to welcome the Fathers and would he thought, leave them free to teach,

though he himself was not likely to adopt their religion. He was not

religiously inclined at all—excepting when he was ill. He smoked

hashish, moreover, which in course of time would be certain to affect

his brain. In the other hand, some of the catechumens had great influence

over him and were always with him.

The return to the capital was like a triumphal procession. A deputation

from the king was sent half-way to meet the travellers—headed by

one of their old converts, who was in great favour at court. Greetings

were given amidst the firing of guns, and the Fathers were assured of

Mwanga’s good dispositions towards them. Many of their old friends,

pages of the royal household, came out to meet them as they approached

Rubaga to tell them that they had fixed upon a place for the mission,

where only the people of the palace were allowed to go. But this did

not suit the Fathers at all., "We manifested a desire," wrote

Father Lourdel, "for a plantation between the palace and the. high

road, where the poor as well as the rich would be able to come to us."

The first audience with the king was everything that could be desired.

Mwanga was, most amiable, and made Father Lourdel promise that they

would never leave Uganda again. Full liberty was given them to teach

and to make converts. "If Mwanga remains in these dispositions,"

said Father Lourdel, “our catechumens will no longer be obliged

to come to us in secret, as of old."

The mission house was begun at once by the king's orders, for their

temporary dwelling was not large enough to hold the crowds that came

to visit them. Through the zeal of the first converts, the number of

catechumens had reached eight hundred—five or six alone had fallen

away."It is quite a common thing," wrote Father Lourdel, "to

see one of the old neophytes arriving with a dozen of his proselytes

behind him declaring that these are not all. He has thirty or so more

in his village at home, whom he will bring another day. He then proceeds

to put them through their paces before us, that we may see how well

they are instructed. They were beginning to despair, they tell us, of

our ever returning, but still they went on with their work of making

proselytes, so that, if they themselves were dead when we came back,

we might still find the Faith in the hearts of the people. Others showed

me rosaries they themselves had made."

The mission house was begun at once by the king's orders, for their

temporary dwelling was not large enough to hold the crowds that came

to visit them. Through the zeal of the first converts, the number of

catechumens had reached eight hundred—five or six alone had fallen

away."It is quite a common thing," wrote Father Lourdel, "to

see one of the old neophytes arriving with a dozen of his proselytes

behind him declaring that these are not all. He has thirty or so more

in his village at home, whom he will bring another day. He then proceeds

to put them through their paces before us, that we may see how well

they are instructed. They were beginning to despair, they tell us, of

our ever returning, but still they went on with their work of making

proselytes, so that, if they themselves were dead when we came back,

we might still find the Faith in the hearts of the people. Others showed

me rosaries they themselves had made."

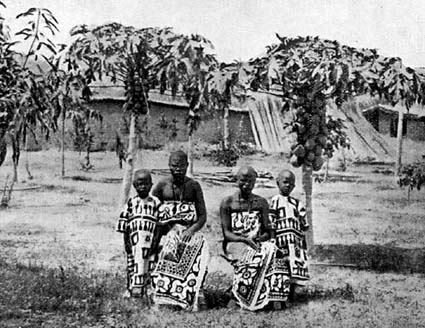

Above: Nephews of Mwanga and their mothers

While Father Lourdel was dealing with the catechumens, and trying to

sort them into different categories, Father Giraud was tending the sick

and studying the language. "He has his hands full," says Father

Lourdel, "for smallpox and the plague are endemic here. Some of

the chiefs," he adds “are hostile, particularly the Katikiro,

or first minister. Before our return he had urged that all the white

men in the country should be put to death, or, at all events those of

the natives who went to them for teaching. Three neophytes of the Protestant

missionaries were seized by his orders and burnt alive. Our return displeased

him greatly, and he refused to see me or to thank me for the present

I had brought him. Seeing in what high favour we were with Mwanga, he

relented sufficiently to send us an ox. This shows that he does not

mean, openly at least, to show himself our enemy."

When the Fathers had left Uganda, Mwanga had been a rather promising

boy; when they returned he had become a rather unpleasing young man.

His face was weak and much less intelligent than his father's; he was

passionate and easily frightened. On his elevation to the throne he

had begun by breaking with the old superstitions of his race and showing

great favour to the Christians, choosing several for the highest positions

in the the kingdom. They had justified the confidence he had placed

in them by saving his life in a plot set on foot by the pagan chiefs

to murder him and put his brother on the throne. For this reason, as

well as others, they were hated by the Katikiro, who had contrived the

plot, but whose prayers and tears had obtained pardon from the king.

It was a well-known fact that in the event of his death, Mwanga had

meant to put one of the Christians, Joseph Mkasa, in the Katikiro's

place and to make another, Andrew Kagwa, general in chief of his army.

It was by the advice of these two men that the Fathers had been recalled.

"Our little mission," wrote Father Lourdel in October, "is

a source of great consolation. Mwanga, it is true, though still friendly,

seems to have completely forgotten that there is another world, in the

enjoyment of this, but that is the only cloud on our horizon. In a few

days I shall be preparing for baptism some twenty of our catechumens,

who have proved their sincerity by five years of perseverance. Nearly

a hundred more are almost ready, but it is best not to go too fast."

The

Protestant missionaries were also profiting by the liberty given by

Mwanga. The news got around that the Anglican Bishop Hannington (left)

was on his way to pay them a visit, and the Arabs, always ready to take

advantage of the fears of the king, suggested a white invasion. The

Germans were threatening Bagamoya and Usagarait; it was easy to persuade

Mwanga that the Englishman, who was said to have a large following,

was part of a European army bent on the conquest of the country.

The

Protestant missionaries were also profiting by the liberty given by

Mwanga. The news got around that the Anglican Bishop Hannington (left)

was on his way to pay them a visit, and the Arabs, always ready to take

advantage of the fears of the king, suggested a white invasion. The

Germans were threatening Bagamoya and Usagarait; it was easy to persuade

Mwanga that the Englishman, who was said to have a large following,

was part of a European army bent on the conquest of the country.

When the Protestant missionaries asked to be allowed to send the mission

boat to meet their bishop, the king sent two of his own men with it

under orders to take the stranger to Msala, at the south of the lake,

and then to come back to him and report. If the report was satisfactory,

he said, he would then allow the bishop into Uganda. Unfortunately the

warning letters from the Protestant mission never reached Bishop Hannington.

He took the fatal step of advancing on Uganda from the Nile, which had

been forbidden, and Mwanga ordered his arrest. The Protestants who went

to the palace to intercede for their countryman were not received, and

on the 26th of October went to Father Lourdel, to see if he could do

anything.

After much pressing Mwanga at last promised to spare

the life of the white man, and to content himself with sending orders

that he should return whence he had come, but either he did not mean

to keep the promise, or the order for his death had already been given.

On the 5th of November the news came that Bishop Hannington had been

murdered in Usoga, with the greater part of his escort. The fact that

Mwanga had dared to kill a white man was a great encouragement to the

Arabs, who commended him for his prudence. (Click

here for more about this)

Below: Bishop Hannington, captured by Mwanga's soldiers and later speared

to death.

A few days later, Mwanga, who had been suffering from ophthalmia, sent

to Father Lourdel for a remedy, which was at once brought to him. The

following day he was better, but Mapera,. before leaving him, gave him

two opium pills, directing him to take them if his eyes should pain

him in the night. The next morning Mkasa, one of the Christian pages,

arrived in a great hurry, with the news that the king had had a very

bad night and was very unwell. Father Lourdel hastened to the palace.

He found Mwanga very sick and in a very bad temper.

A few days later, Mwanga, who had been suffering from ophthalmia, sent

to Father Lourdel for a remedy, which was at once brought to him. The

following day he was better, but Mapera,. before leaving him, gave him

two opium pills, directing him to take them if his eyes should pain

him in the night. The next morning Mkasa, one of the Christian pages,

arrived in a great hurry, with the news that the king had had a very

bad night and was very unwell. Father Lourdel hastened to the palace.

He found Mwanga very sick and in a very bad temper.

" The first pill you gave me," he said, "made me sleep,

but the second made me very giddy, and I have been ill ever since. "

Father Lourdel assured him that the effects would wear off, but the

king was under the impression that he had been poisoned, and that he

was dying. He refused to touch any of the remedies suggested, and groaned

despairingly. Naswa, one of the royal princesses, who had been doctored

successfully by Father Lourdel some days before, assured Mwanga that

she had taken three opium pills and had been none the worse. She at

last induced the terrified invalid to take some of the citric acid which

Mapera had brought, with the result that he recovered rapidly. But Father

Lourdel's reputation had suffered a blow from which it would not be

easy to recover, and Mwanga's suspicions were likely to form a strong

handle for his enemies against the Fathers.

On the following Sunday, when Father Lourdel went to the palace, he

was told that the king’s ophthalmia was quite cured, and that he

was in his usual health. He had been talking to his chiefs the greater

part of the night. A little boy, one of the king's pages ran up to Mapera.

"You would not baptise me when I asked you to last week,”

he said; “now you will be sent away, and what shall I do ?”

"Sent away?" exclaimed Father Lourdel. "Yes," said

the child, "the king said very bad things about you last night.

He thinks you tried to poison him in revenge for his having killed the

Englishman, and that you want to put another king on the throne, because

he will not adopt your religion. He is going to drive out all the white

men, and perhaps kill them."

"Having been told that I could not see the king, as he was engaged

with his chief," wrote Father Lourdel, "I sat down in great

anxiety to wait. Presently the door opened, and one of the pages came

out in the greatest distress. Joseph Mkasa, chief of the pages, had

suddenly been arrested and carried off to be burnt alive. The king had

declared that it was he who had advised me to give him the medicine

that had so nearly caused his death, and that he had warned the English

of the plot to kill them. Moreover he had dared to say to Mwanga himself

after the murder of Bishop Hannington: "Why do you kill the white

men? Mtesa, your father, never did so."

"I went back sorrowfully to the mission,” adds Father Lourdel,

"to tell the others what was happening. The future seemed dark

indeed, and we all took to our prayers.”