Uganda

is remarkable for the beauty of its scenery and its climate, which is

cool compared with other countries in the same latitude, the temperature

varying between 57 and 91 degrees. The dry and the rainy seasons are

neither altogether dry nor altogether rainy, to the great advantage

of the vegetation. The banana palm, which grows in abundance, furnishes

food, wine(1), rope and even soaps(2) to the natives. Their dwellings,

cleverly built of logs and reeds and thatched by expert workers in such

a manner that they are proof against sun and rain, look rather like

large cones. The establishment of a chief is composed of several hundred

of these buildings, close together; the principal one, in which the

great man lives, is surrounded by a spacious courtyard, enclosed by

a handsome reed paling. The palace of the king consists of from four

to five hundred huts, some of them over twenty yards in diameter.

(1) "Mwenge" the favourite

drink of the people, is made from fermented banana juice.

(2) The ashes of burnt banana skins, mixed with fat, are made into a

primitive kind of soap.

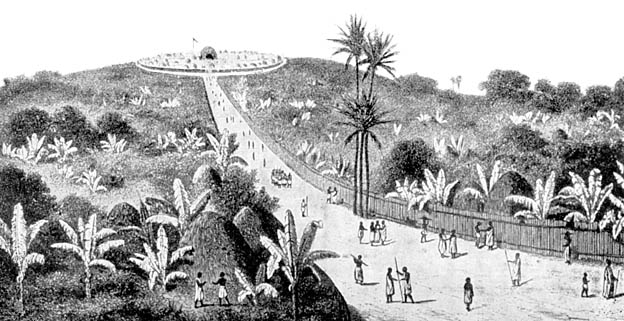

It was the custom of the king to change his residence periodically,

and when the White Fathers arrived in Uganda, the court was on the slope

of the hill called Rubaga.

Rubaga—capital of Uganda

The

people of the country were decently clothed in the beautiful red bark-cloth,

for the manufacture of which they were famous, worn by the men as a

large cloak knotted on the right shoulder, and by the women as a kind

of a tunic, wrapped round the body under the arms, and secured at the

waist by a sash of the same material. The cloaks of the men were frequently

made of the skins of goats, antelopes, or leopards, made supple and

soft by dressing, and so cleverly sewn together that the seams were

invisible. Those of the upper classes wore beautifully made sandals

of buffalo-hide. They were a cleanly people, who believed in frequent

washing, and were consequently devoid of the unpleasant odour characteristic

of many of the native races. Besides the dressing of leather and fabrication

of bark-cloth, the country produced its own knives, hatchets, spades,

and many ornaments. The profession of smith, like all the other special

crafts, was hereditary in certain families. At all kinds of basketwork

the natives were adepts, and they produced musical instruments of various

kinds.

The method of government in Uganda was also peculiar to the country.

The Kabaka, or King, was all powerful; he was supreme master of the

kingdom, and could dispose of his subjects at his pleasure. When, for

instance, Father Lourdel asked for a place in which to establish the

mission, Mtesa settled on a certain banana plantation on which there

were several huts, giving the owners notice to quit. Father Lourdel,

aghast at what seemed such a crying injustice, was anxious to make some

compensation to the poor people who had been turned out in his favour,

but he was assured that it would be looked upon as an insult to the

king to consider as injured those who had made way for his guests. The

evicted tenants, moreover, turned out quite cheerfully, as if it were

the most natural thing in the world.

The kingship was hereditary, though it lay, with the chief men in the

kingdom to decide which of the dead king's sons should succeed him.

If they differed there was usually war.

"Every morning,” wrote one of the missionaries, "the

wide alley leading to the king's court is thronged with people. The

chief men of the kingdom, going to pay their respects to royalty, deputations

from the chiefs, or kinglets, of Usoga, accompanied by bands of musicians,

playing flutes, drums, reeds, pipes, and harps, the wild harmony of

which is not displeasing, together with the representatives of rulers

from the western shores of the Lake, bringing ivory, salt, and other

offerings.

"Privileged visitors are admitted to the courtyard before the hut

of the chief minister, where they wait for the appearance of the king.

There is no fixed hour for audiences, but good manners prescribe an

early arrival and patient waiting till midday. From time to time one

of the king's pages comes to see who is there, and to report to his

master. At last he comes back with the message: 'the king is there’;

the chief minister rises and hastens to the audience chamber and the

visitors follow. If they are numerous, it is the business of the porters

to sort them out—sometimes with the help of their wand of office.

“The resultant tumult pleases the king, who sees in it a token

of his popularity. He stands at the door of the royal hut, which is

open. Distinguished guests alone are allowed to enter; the rest sit

broiling in the sun outside—to them a small matter, for no sun

is too hot for an African. When the king is unwell, he receives reclining

on a couch, otherwise he sits on a kind of primitive throne, with a

carpet of lion-skins beneath his feet. If he has a private communication

to make to anyone, he beckons to him to approach and whispers in his

car, the orchestra playing vigorously the while.

"If the king laughs, all laugh, if he is serious, all are serious,

if he weeps, all weep. The natives do this in the most natural manner

possible. Sometimes he has to decide some special case, though as a

rule this is done by the chief minister —and then it is interesting

to hear with what ingenuity the claimant pleads his cause. There are

no police in Uganda, but any number of executioners, to whom those condemned

to death are given up, to deal with as they please. As the aim of these

men is gain, they usually torture their unhappy victims as long as there

is anything to be got out of them, or of their relations, who may be

induced to pay something to have them put out of their pain. The politeness

of the people is matched by a strange callousness to suffering, especially

when the sufferer is a slave. I saw men bursting with laughter over

the sufferings of a slave who was dying of hunger, having begged in

vain for the food that would have saved his life.

"The respect of the natives for authority and their blind obedience

to it, together with their natural courage and energy, make them easy

!o govern in time of peace, and excellent soldiers in time of war.

"The royal family consists of the Namasole, or queen-mother, and

the Lubuga, or queen-sister, both highly privileged and greatly respected.

The king's household comprises the chief officials, the royal pages,

the soldiers of his guard, and many servants.

"Immediately below the king comes the Katikiro, or chief minister,

and below him all the governors of the different provinces. Beneath

these are the 'king's men,' or officers. If the king wants to honour

one of his subjects who has done him a service, he confers on him a

property and makes him a 'king's man.' He can then wear the necklace

of honour and have a guard, according to his means. From these men the

king chooses his chief officials, and the sons of both categories become

his pages."

Slavery, polygamy, and their attendant evils, together with the influence

of the witch doctors, who claimed the. power of divination, and were

held in awe and veneration, were the chief obstacles the missionaries

had to contend with. The people believed in good spirits, from whom

all good things came, and evil spirits, who were responsible for all

the ills of humanity. Each spirit was represented by a witch doctor,

who claimed to be in communication with him, and who was consulted in

every difficulty, and propitiated with presents.

Soon after their arrival, the king sent Sabakanzi, one of his own relations,

with presents to the Fathers, inviting them to a solemn audience on

the 27th of July. The audience was described by one of their number.

"We started at seven, with our presents, and Mtesa's flag borne

before us. The natives admired our habit immensely, and examined us

with interest on the way. When we reached the palace, as the sun was

hot, we were invited into a hut and mats were spread for us to sit on.

After an hour's wait, during which we watched the royal guards drilling

outside, a page came to fetch us and led us to the audience chamber.

The king, wearing the usual mantle, knotted on the shoulder, was reclining

on a couch, surrounded by his chief men, sitting on mats. We saluted

his Majesty and were invited to sit down. Mtesa looks about forty; his

face is most intelligent, not at all like the usual negro type. He has

an open forehead and large black eyes, speaks little, shows perfect

self-possession, and rarely betrays his thoughts.

"At first we were all rather constrained, no one daring to speak

before the king did. Then we sent for our presents, consisting of the

things most prized in the country—swords, helmets, knives, mirrors,

gold buttons, etc. Father Lourdel unpacked and exhibited them, the king

showing no emotion. But when they had been examined and removed, he

began to thaw, asked, after Father Livinhac's health, gave us to understand

that he was pleased and satisfied, and thanked us. Some of the courtiers

said kind things about us, and Toli, a native of Zanzibar, who had been

in France, and had befriended Father Lourdel on his arrival, suggested

that we would be the better for a larger house. Mtesa listened with

approval, and agreed to Toli's request that he would name someone to

collect the materials and direct the building. Then, with the customary

wave of the hand, he dismissed us."

The building was begun at once, on a plan made by Father Barbot. Though

built, like everything else in Uganda, of wood and reeds, its unusual

shape excited much admiration when it was finished, though the king's

builders could be hardly induced at first to depart from their usual

lines, and declared that the fathers were mad to think it possible.

It was about seventy feet long with two wings; in one was the chapel;

in the other the refectory and kitchen; the centre building contained

rooms for the Fathers.

The first caravan of Missionaries to Central

Africa

(Left to Right)

Back :

Frs Deniaud, Delauney, Dromaux, Pascal and Brother Amantius

Front : Frs Augier, Girault,

Livinhac, Lourdel and Barbot

Though

Mtesa had shown himself friendly, he had been very reserved; it had

been impossible to judge of his real sentiments. The Fathers were therefore

surprised, a few weeks after their visit, to receive a, message from

him declaring that he wished to know and study their religion. Father

Lourdel, who had been given the name of Mapera (mon pére) by

the natives, went next morning to the palace and spent an hour with

the king over the catechism. Mtesa proved himself a most attentive and

intelligent pupil, refusing to go on until he was sure that he had thoroughly

grasped each question. "If our religion consisted only of doctrine,"

wrote Father Livinhac, "Mtesa, would, I think, soon be a fervent

Catholic. But there is the moral side, and that is another thing."

One day the king expressed a desire for an accordion. Luckily the Fathers

had one in their stock. It was sent for and Mtesa demanded that it should

be played. Father Lourdel, as usual, stepped boldly into the breach.

His knowledge of music was limited, but he succeeded in making a good

deal of noise, which delighted the king. The order went forth that there

were to be no audiences that day, and Father Lourdel's powers of improvisation

were sorely put to the tax during the hours that followed.

The next day Mtesa sent for the two Fathers to come to him in secret,

and asked them to go on a deputation to France to put Uganda under French

protection, as the Turks were threatening his northern frontier. Father

Livinhac was aghast. They had come to Uganda, he told the king, as simple

missionaries; they had no authority to meddle with politics, and it

would be impossible for them to return to France at present. They would,

if the king wished, signify his desire to the French consul at Zanzibar,

but could do no more. Mtesa was astonished and hurt at what he considered

a refusal to oblige him. It was apparent that his readiness for instruction

covered a desire to use the missionaries as political agents.

The Fathers were more or less in disgrace, but at this moment Mtesa

fell ill, and sent for Father Lourdel to doctor him. His prompt recovery

filled him with respect for the amateur doctor's remedies, to which,

he said, he would confine himself for the future. Mapera was in favour

once more, and was called upon to continue the instructions.

One August afternoon the king sent for Father Lourdel and demanded to

be taught the rosary The instruction went on late into the night, by

the light of two great fires, one in the room and one in the court-yard

outside. When he had mastered the prayers of the rosary, Mtesa asked

to go on with the catechism, and Father Lourdel explained to him the

Catholic doctrine on the remission of sins, the Church, Purgatory, and

Heaven. The king was delighted, and when he fully understood it, explained

the matter clearly to his chief men, who were present. The idea of Heaven

especially appealed to him. "Tell me something more about Heaven,"

he kept on repeating.

It was late when Father Lourdel returned to the mission house bringing

the good news that Mtesa seemed quite convinced that the Catholic Faith

was the true religion. The next day the king sent two goats, with an

invitation to come back again that evening. When he arrived Mtesa seemed

sad and thoughtful. "Does the king find our religion too hard?"

said the priest to Toli. "No," answered Mtesa, who had heard

the question, "that is not the cause of my sorrow." The same

day, a native, who had come to the mission for instruction, had said

to the Fathers, "The king wants to be of your religion but the

chief men will never allow it."

The instructions went on; Father Lourdel was continually being sent

for to the palace. The question of mortal sin was a great stumbling

block to the king, and the Catholic standard of purity. "What power

enables you to live the life you do,” he asked one day of Father

Lourdel. "The grace of God," was the answer. Mtesa seemed

lost in thought. Many of the chief men were angry at the turn things

were taking. "Begin by sending away all your, wives," they

cried one day, "and then perhaps we will follow suit."

Calumnies were circulated against the missionaries. They were concealing

arms in their house, they were digging mines under the royal citadel;

they had bought three hundred slaves, and were teaching them to shoot.

Unless they were got rid of now, in a few years they would be in possession

of the kingdom. Father Lourdel took the bull boldly by the horns in

their presence and in that of the king. "How can you, who are so

intelligent, believe such nonsense?" he asked Mtesa. "You

know well that we have given all our arms, to you. How could we dig

mines without being seen or heard? Send reliable men to search the mission

house, and they will tell you that our three hundred slaves consist

of some thirty children, whom we have ransomed to bring up. But if you

are afraid of us, say so openly, and we will leave Uganda and go somewhere

else."

For a time this silenced calumny. On the third of October, after having

gone through the whole catechism, Mtesa asked to be baptised. "If

I baptise you," replied Father Lourdel, "you will have to

send away all your wives but one." That was a hard law, said the

king, he had not the strength to comply. "Pray for strength, and

it will be given you," was the answer. The king asked if the law

could be stretched sufficiently to allow him two wives. “You now

understand our religion” said Father Lourdel, after answering his

question,"it remains with you to decide. We will never force you.

Jesus Christ will only accept a heart that gives itself freely.”

It was clear that Father Lourdel had acquired a wonderful influence

over the king. It was he to whom Mtesa always appealed, and by whom

he wished to be instructed. The fact was due to the united prayers of

the missionaries, who did not care which of them did the work as long

as the work was done; the others rejoiced over Father Lourdel's success

as if it were their own. But it was due too, to his fearless character,

his presence of mind under trying circumstances and the ease with which

he spoke the native language.