In spite

of all the precautions taken, the many visits to the missionaries began

to excite suspicion. What had these white men come for? What were their

intentions? Were they forerunners of a European army, preparing the

way for the conquest of the country? The Fathers knew through their

catechumens among the king's pages, that these questions were being

continually discussed at court.

The Arabs, who had regained a good deal of influence over Mtesa, did

their best to fan the flame. The white men had certainly designs on

the country, they said, would it not be a good plan to defeat their

influence by making Islam the religion of the country? The king had

only to order all his subjects to attend the Mosque at Rubaga to find

out how many had been seduced by the strangers.

This last suggestion appealed to Mtesa. Invitations were sent out for

a great muster to be held in the capital on Friday, the 9th of September.

One of the catechumens warned the Fathers, who at once realised the

gravity of the situation.

Among those present would be at least a hundred and fifty of their converts—for

whom it would mean persecution and death.

It was agreed that Father Lourdel should make a desperate attempt to

avert such a catastrophe. On the day fixed, he succeeded, not without

difficulty, in making his way into the palace—to the consternation

of the Arabs and the great embarrassment of the king.

A whispered consultation resulted in the decision to postpone the business

to the following clay, and the meeting was soon broken up. The next

day, however, Father Lourdel was there again. The annoyance of the Arabs

was great, but the day after was Sunday, when the Fathers never went

to the court, and they would be free to carry out their project. So

once more the time was passed in the discussion of trifles, without

any allusion to the matter in hand.

But on Sunday, directly after Mass, Father Lourdel hastened to the palace,

arriving just as the proceedings had begun. It was obvious that the

order would have to be given in his presence or not at all. "There

has been," said Mtesa, "as you all know, a bad outbreak of

plague in the country. I have been assured that if we pray with the

Arabs it will cease. We will now go all together to the mosque."

Father Lourdel fell on his knees before him. "You are a great king,"

he said, "and a great king does not force his subjects into religion.

God demands a willing service. If there are any who wish to pray with

the Arabs, let them do so, but I beseech you do, not use constraint."

The Arabs were furious. "Is it possible, 0 King,” they cried,

"that you will let yourself be dictated to by a stranger? You are

master here, and no one has the right to withstand your will. The white

men want to conquer your country. Their religion is a religion of lies.

They teach your subjects only to withdraw them from their allegiance

to you. There is no God but Allah, and Mohammed is his prophet."

Father Lourdel sprang to his feet with an impulse born of desperation.

"If the religion of Christ is a religion of lies," he cried,

holding up the Gospel, "and if theirs be true, let God be the Judge.

Let them bring wood into the courtyard, and make a great fire. I will

go through it with the Gospel in my hand; let them do the same with

the Koran."

The king was thunderstruck. The Arabs, who dared not accept the challenge,

suggested sorcery. But the zeal and courage of Mapera had won the day,

and it was decided that everyone should pray as he pleased. The Protestant

missionaries, who had many converts at Rubaga, came that evening to

thank Father Lourdel for his intrepid defence of Christianity.

Thanks to the liberty thus obtained, the Fathers were able to continue

their work, and during the early months of 1882 the number of converts

increased steadily. In April, during an outbreak of cholera, they devoted

themselves to baptising the dying.

In spite of his regard for Father Lourdel, Mtesa still looked on the

strangers with suspicion, and the calumnies of the Arabs continued.

"What are they saying to my subjects to induce them to go to them

so often?" he would ask of his chiefs. "Will they never go

away?" The people too, realizing that the white men were no longer

in favour, ceased to respect them as Mtesa's guests. The mission was

frequently broken into by thieves during the night, and at last the

Fathers had to take it in turns to sit up watching, lest their house

should be set on fire or robbed. Complaints to the king met with no

response, indeed they sometimes wondered if he were not behind these

midnight maraudings, and if their object might not be to disgust them

with the place and induce them to leave it.

The impending persecution had only, it seemed, been retarded by Father

Lourdel's victory over the Arabs. It was whispered that it would break

out in all its fury on the return of an expedition which Mtesa had sent

to Usoga. What effect would it have on the catechumens still so young

in the Faith? What could they themselves do to avert it? Would their

departure save their converts? The Fathers prayed for guidance. The

question was decided by Cardinal Lavigerie, who, on the murder of the

White Fathers in the Sahara, had issued orders that no one henceforward

was to expose himself deliberately to almost certain death.

One morning, accordingly, Father Lourdel went to the king and told him

that, for reasons connected with health and business, they had determined

to leave Uganda for a time. Mtesa seemed astonished, but he granted

them the boats they asked for to carry them across the lake, and gave

them as a parting gift a magnificent elephant's tusk. Taking their ransomed

children with them, they abandoned the mission, arriving at Kagei on

the eve of Epiphany, 1883.

The question was now to settle somewhere else, and as Father Livinhac

was ill with fever, it fell to Father Lourdel to explore the country.

Taking Father Girault with him, he set off to Bukumbi, at the south

of the lake, hoping that it might be possible to establish a mission

there. Kiwanga, the king of Bukumbi, received them with great friendliness,

promised them a property, and, to seal the compact, suggested that Father

Lourdel and his son, Mazingue, should become blood-brothers. Two cups

of pombe (the native wine) were accordingly brought in, a little incision

was made in the breast of both men, and a drop of blood from each allowed

to fall into the two cups. When each man had emptied the cup which contained

the blood of the other, the ceremony was complete. A terrible curse

is laid on the breaker of this bond, regarded as sacred.

"The inhabitants of the country seem a peaceable and simple folk,"

wrote Father Lourdel to Father Livinhac, "and we shall be sufficiently

near Uganda to be able to correspond with our converts there."

After helping to found the mission, Father Lourdel took some of the

orphans, whom he had left at Kagei, to the mission of the White Fathers

at Kipalapala, some five miles from Tabora, and returned with the rest

to Kikumbi, stopping on the way to visit the famous king, Mirambo. "It

is most important to secure his alliance," he wrote, "the

whole district between Bukumbi and Tabora belongs to him, and is free

from Arab domination." The rainy season had set in and the journey

was difficult. Father Lourdel had a bad attack of fever, and became

so ill that for a time they could not go on, but as soon as he was able

to crawl, he went to see the king. "He is one of the finest negroes

I have ever seen," he wrote, "taller than most men, brown—not

black— and magnificently proportioned. He spends his time, when

he is not at war, hunting lions and leopards. The hut in which he received

us is hung with their skins. He greeted us with great courtesy, presented

us with an ox and a goat, gave us a guard, and even insisted on accompanying

us part of the way himself."

At Bukumbi things were progressing. The Fathers had left their temporary

dwelling, had inaugurated the mission of Our Lady of Kamoga, and were

building a small house. "It stands between two great masses of

rock," wrote Father Lourdel to his brother, "inhabited by

a colony of the ancestors of our friends, the Darwinists, who make a

great deal of noise. Our food consists of rice and sweet potatoes, badly

seasoned. Kiwanga continues to be friendly; the people are less intelligent

than those of Uganda; they show little inclination for religion, but

much for being doctored. We have opportunities of exercising charity

in the treatment of diseases, and the dressing of terrible sores."

The little group of Uganda orphans, he adds, will form the nucleus of

a Christian village. He asks for prayers. (His brother was a Carthusian.)

"The missionary may move heaven and earth, but God alone can make

his efforts fruitful. When one is weak in body and soul, one feels like

a child trying to lift a huge mass of rock to carry it up a hill. At

such moments it is faith alone that carries one on."

Since he left Uganda, Father Lourdel had been suffering greatly, and

now he became seriously ill. He was not past cure, but a change of climate

was absolutely necessary, and it was decided that he should return for

a time to France. In July 1883, he was on his way back to Tabora, but

on hearing that Cardinal Lavigerie had ordered the foundation of another

mission, midway between Tabora and Lake Nyanza, he begged off. The position

of Kipalapala was healthy and would supply all the change of air he

needed; he might be useful for the foundation.

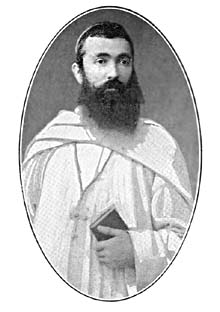

As

a matter of fact he was necessary for the foundation. Father Livinhac

had been made Vicar Apostolic and Bishop of Pacando, and had gone to

Algiers for consecration. (see photo,left, supplied by

Robbie Dempsey))

As

a matter of fact he was necessary for the foundation. Father Livinhac

had been made Vicar Apostolic and Bishop of Pacando, and had gone to

Algiers for consecration. (see photo,left, supplied by

Robbie Dempsey))

On his way he had visited Mirambo, and had obtained from him a site

for the proposed mission to Ukune. "Come whenever you are ready,"

said the king,"I have already told you that I am glad to have you

in my country."

At this moment there arrived at Kipalapala a band of young men from

Uganda, who, determined not to die without having received the Sacraments,

had set off in pursuit of the Fathers. They had gone to Kamoga, where

the missionaries not daring to keep them, for fear of Mtesa, had sent

them on to Tabora. A few days later, they were joined by others, and

their delight at finding their beloved Mapera at Kipalapala was touching.

Those whom they had left behind, they said, were persevering bravely.

During a recent outbreak of the plague, when everyone had fled, they

had remained behind to baptise the dying, and had succeeded in converting

many of their friends and relations. Mtesa was very ill, and his dispositions

were not improving. There was great distress when they heard that Mapera

was about to set out for Ukune, and they all begged to go with him.

"We have left our country and our kinsmen to find you," they

said, "and now you are going away.” It was impossible to take

them all. Father Lourdel chose out six, and left the rest at Kipalapala.

On April 3rd he reached Mirambo's capital. The king was ill, and Father

Lourdel was able to help him, though he recognised that the malady was

incurable. “He received me,"' he wrote, "with his usual

courtesy and kindness, sitting in an arm-chair." The site at first

chosen for the mission, he thought, was too much exposed to the attacks

of the Watuta, a robber tribe with whom he was constantly at war. He

would give them another, near the principal village of Ukune, where

they would be in greater safety." On it they found three large

huts, which they occupied while the Uganda converts helped to make bricks

for the construction of the mission house. Father Lourdel ransomed a

few captives taken in war, one of them a wild little fellow who had

been brought up among the Watuta, and who took some timing before he

fell into line with the rest. As Father Giraud, who was to join him,

had not yet arrived, he spent his time teaching the little household,

preparing some of the Uganda catechumens for baptism and building the

house. "I have no alarm clock," he wrote, " I get up

when the birds begin to sing. The old cock, whom I secured to act as

caller, has no idea of time. At daybreak we pray together, after which

my people go out to work, while I make my meditation and say Mass. After

breakfast I go out with them, to work with them and direct them. I have

stuck a long pole in the ground in the middle of the courtyard. When

its shadow reaches a certain point, we stop work and rest, while I give

a lesson on the catechism; then we all begin again till sundown when

we sup by the light of a primitive lamp, kept going by butter! Then

come night prayers and we go to sleep each on his mat.

By the end of July the building was finished and the mission christened

by the name of St. Mary of Ukune.

It was uphill work. There was a now language to be learnt, the habits

and customs of a new tribe to be studied, a new religion, in which the

witch-doctors played a great part, to be considered, so that Father

Lourdel had plenty to do until June when Father Giraud arrived. Early

in September Mirambo, on a fighting expedition, came to visit the mission.

He was interested in everything, and remained for an hour talking to

the Fathers. The witch-doctors were busy with incantations, aspersions,

and the sacrifice of an enormous ox, to ensure his success and the death

of his enemy, Kapera. The war was still going on in November. when Father

Lourdel was sent for in great haste to go to Mirambo, who had been suddenly

taken ill. He set off at once, but was too late. The king, whose friendliness

had helped the missionaries so much, had died the night before.

Throughout the two years that had elapsed since their departure from

Uganda, Father Lourdel had never ceased to hope that some day they might

be able to return. One of his catechumens, whom he was preparing for

baptism, was destined to go home to tell the rest to wait patiently

and with courage till the Fathers were able to go back again. In December

they heard from an English traveller who was passing that Mtesa was

dead, and that the chiefs had chosen Mwanga, the youngest of his four

sons, to succeed him. Mwanga, who was only sixteen when they had left

Uganda, had been a great friend of Mapera's, and it was generally believed

that he would recall the Fathers. "It would be advisable,"

wrote Father Lourdel, "to go back at once, while the king is still

in dispositions to welcome us; to wait would be fatal."

If the death of Mtesa made a return to Uganda possible, the death of

Mirambo threatened the existence of the mission of St. Mary of Ukune.

Mirambo's brother, who succeeded him, was far below him in intelligence

and courage, and the great kingdom which Mirambo had built up began

to fall to pieces. The war with Kapera was still going on, and things

might become serious at any time. Father Girault*, who was at the mission

of our Lady of Kamoga, was deputed by Father Livinhac to go to Ukune

and talk matters over with Father Lourdel. After careful deliberation

it was finally decided to leave, at least temporarily, the mission at

Ukune, and to return to Uganda.

*Ludovic Girault, in charge of the mission at Kamoga—not

to be confounded with Fr Pierre Giraud who was working with Fr Lourdel

at Ukune

Fathers Girault and Giraud were to go to Kamoga with the youngest orphans

and part of the baggage, while Father Lourdel was to seek out the King

to tell him of their decision, and to leave their house under his protection,

and then to go on to Tabora to get what was necessary for the establishment

of the Uganda mission.

It is easier to make plans than to carry them out—especially in

Africa. Father Girault, who went off first, nearly fell into the hands

of the ferocious Watuta on his way to Kamoga and Father Lourdel had

a regular chapter of adventures on his way to find the king.

In the March of 1885, leaving three of his Uganda converts in charge

of the house, he set off —to find that the road was impassable

through floods. They tried another way, and after days of wading through

swamps and struggling through tangles of tropical vegetation, arrived,

half devoured by ants, at Kanongo, where the king was installed. He

was much displeased when told of the proposal to leave Ukune. "If

Ukune is not safe," he said, "choose another part of my kingdom."

To soothe his feelings, Father Lourdel offered him his gun, but the

present had not the desired effect. He demanded two thousand cartridges

for his own two guns, and became very disagreeable. He suspected, it

appeared later, that the Fathers, like a good many of his other friends,

had gone over to his enemy, Kapera.

Father Lourdel started once more on his travels—this time to Kipalapala.

Unyanyembe had become one great swamp, and it was still pouring—in

a tropical deluge. "We were like ducks," he wrote, "half

swimming and half walking, through glutinous mud. I was dreaming of

the warm fire and the good meal awaiting us at the end of the journey,

when Gabriel, my companion, suddenly informed me that he did not know

where we were. We were lost!

Suddenly we began to sink; we were in a quaking bog. By dint of desperate

efforts we dragged out the donkey, who was fast going under, and presently

reached firmer ground. The sun was setting when we saw the hill of Kipalapala

in the distance, and the darkness fell as we reached a little village

where we tried to induce someone to be our guide. They all refused,

being afraid of lions and leopards, and we struggled on alone. At last,

at ten o'clock, we reached our goal, and forgot all our miseries in

the warmth of the welcome we received."