PAGE

55

Fr TOM DOOLEY WF

Prisoner of War

1940- 1944

The following was written by Fr Tom Dooley at the behest of Eugene MacBride.

1 A few days ago, 25th August, to be exact, my memory was stirred by the fact that forty years had passed since we were released from St. Denis. But memory was not stirred as much as all that . . . there are still a lot of gaps. A group of us together would be able to dig out quite a lot. But I am on my own. Still you can have what I can give. |

2 We were not long back at Kerlois, perhaps a couple of days, before we were ordered to repot to the German Kommandatur in the village of Hennebont. The emotions of the group? Difficult to say. A certain amount of apprehension but no hysteria. The guard was changed while we were in the office and some of us thought it was the firing squad. I think in situations like that the mind and the emotions do not work in parallel. We could accept the idea of a firing squad but emotions would not have started registering until we were looking down the barrels. Or perhaps we were just plain dumb. So I have to come back to apprehensive but not hysterical. Those with Irish passports were allowed to return to the seminary and the rest of us were told that we would be detained . . . just like that. We were then marched off to a military camp. We were the only prisoners there and, of course, many came to stare at these strange specimens dressed in douillette and shovel hats.

|

3 |

4 I cannot. remember clearly how the first news of our situation reached home. I believe some news came to the WFs in England from Portugal. The. news was brief enough . . . . all alive and well in the hands of the Germans. It took about six months or more before we had direct contact with our families. From our side we were allowed to write letters of twenty five words on special forms. Later we were allowed to write normal letters but on special forms. And, of course, our families used the official forms for prisoners of war. Once things got a bit organised we were allowed to write three letters a month. There was no regular postal service in the sense that you could expect an answer to your letter within a certain period of time. It seemed to be a haphazard sort of business. Maybe there was some sort of planning but I never noticed it. And for the six months before our release we had no communications with our families. I suppose it was nearly a year before we started receiving parcels regularly from the Red Cross. I am rather vague about that although the parcels were an important feature in our lives and a distribution of parcels gave a tremendous boost to our morale. The general idea was that we would receive a parcel every week. At times it did work out that way but there were many interruptions and some long periods without anything at all. The parcels came mainly from the British Red Cross but we did receive them too from other countries especially Canada, America, S. America . . . . . The spice of life. We have always been very grateful for what we received from these organisations. More than a few of us would not have made it without them.

|

| 5

Our families were allowed to send us individual parcels of clothing. This did not work out too well. Many of the parcels went missing and some were pillaged before they reached us. We received cigarettes from the Red Cross. When things were going well we would receive a ration of fifty per week. Needless to say we often missed out on them. We were also allowed to buy a ration of French cigarettes - sixty a month. We had some money. Once again it took some time to organise but eventually the British government was lending us £I-50 per month. Of course the buying power was much more than it is today but I just cannot remember the price of the goods available for sale in our canteen. But the loan was enough to buy our cigarettes once a month and the half litre of very poor quality wine we were allowed each week and other odds and ends like soap and razor blades. The money we received was a loan but nobody ever asked us to return it. |

6

When we reached St. Denis the two priests in the group started to organise a course of study for us. We made up two groups: one had already completed Philosophy and were ready to start Theology and the other still had a year of Philosophy to do. During our four years as Hitler's guests we covered a two year course of the main subjects (major courses). We owed a lot the Frs. Maguire and Moran who kept our noses to the grindstone in spite of all the difficulties. The Philosophy group had their books sent to them from Kerlois (which was eventually taken over by the German army). Books on Theology were not so readily available . . . . we had to manage on one copy of Arregui's Summary . . . . for students and professor. Eventually we were able to get some books from Germany through the good services of the German Commandant of the camp in spite of this we were always short of reading matter. So we were out of normal seminary life for a period of five years but our studies in the camp counted for two years. A loss of three years. But strangely I have never heard anyone bemoaning the fact. We were not too enthusiastic about doing a full novitiate when we got back but even there I think our grousing did not go beyond the normal. We were photographed from time to time for official purposes (I still have my identity card). Many of the visiting officials arrived with cameramen. But generally speaking we were not allowed to have cameras. I say generally speaking since it is possible that permission was granted for special occasions. It is more than forty years ago!

There was a character in the camp who from time to time would go around like an Old Testament prophet shouting 'Another three weeks' We tolerated him because he was saying out loud what most of us thought or at least hoped. And if you keep saying ‘Another three weeks’, well, the day comes when you are right. We had all the news bf the Normandy landing (together with clouds of rumours) and of course expectations grew. The build-up in Normandy took a very long time, at least from our point of view. And then came the breakthrough. It was the film of the 1940 Sedan breakthrough running backwards. And then one night someone came running into the room waking us up shouting 'They have gone!' And that was that. My stomach heaved; I did not realise I was so physically keyed up. But they had gone.

|

7 |

8

But I have no regrets and I have not heard any of the others voice such regrets But to be more specific about the credit side is more than I can do. I think one is constantly being made by one's experience . . . made or unmade, since there is something more than the objective experience involved. For example, I have often wished I had been sent straight to Africa after ordination, to a bush mission station, instead of being involved in teaching. Or if I had to be involved in teaching I would have liked a spell at one of the universities first. If you like to put it that way perhaps I regret that one or other of these things did not happen to me. But I do not regret having spent some time as a prisoner. Be charitable enough to say that I have a very bad, uneducated typewriter and that I am a very busy man. I have not answered your questions about unusual characters and unusual happenings. There were plenty of both. If ever you get the chance to listen in when a few ex-St. Denis men are together you will hear plenty. And there should be room to join us because the rest tend to leave us to ourselves. Perhaps they have heard all the stories before ad nauseam. |

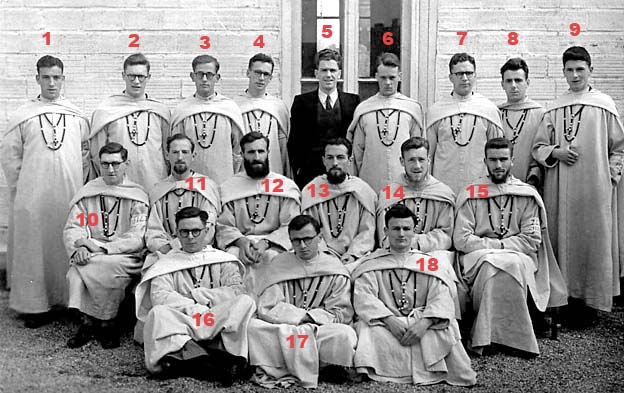

| 1.Geddes Gerry | 2.Gerry Taylor | 3.Gerry Napper | 4.Tom Rathe | 5.Vincent Batty | 6.Dick O'Brien | 7.George Fry | Kevin Wiseman | 9.Francis Paul Moody |

| 10.Gerry Pitt | 11.George Penistone | 12.Jack Maguire | 13.Tom Morton | 14.Tom Dooley | 15.Tom O'Donnell | 16.Peter Walters | 17.Joseph O'Brien | 18.Francis Copping |